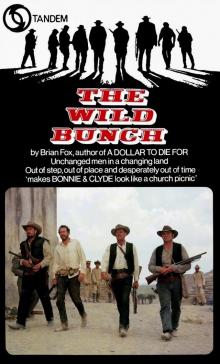

The Wild Bunch Read online

Page 6

Lyle took a step toward him.

“Who in hell do you mean—they?”

Sykes still held the heavy buffalo gun. His cackling laugh brought them all around.

“They? Why they’re just plain and fancy they.”

He began to dance, jigging, kicking up one foot and then the other, his laughter shrill and malevolent.

“Caught you, didn’t they? Tied a can to your tail, didn’t they? Let you in and waltzed you out with lead. Oh my, what a big, tough bunch you are. Too good to ride with an old man. Big tough bastards, standing around with a bunch of holes—a big thumb up your ass and a big grin to pass the time of day.”

Tector Gorch jumped toward him but the old man brought up his gun. He backed a few steps, stumbled on a stone and fell, still laughing.

Tector sprang again but Pike was in the way, his gun pointing at Tector’s face. His voice was level, quiet.

“Railroad men—Pinkertons—bounty hunters.” He paused, then very softly added: “Deke Thornton.”

Sykes’ laughter cut off. He stared at Pike, rose slowly to his feet, spoke as if he knew he had not heard right.

“Deke Thornton? You don’t mean Deke was with them?”

Pike nodded.

Lyle Gorch was not interested in Deke Thornton. His slow mind was still on the washers.

He shouted, “How come you didn’t know? Didn’t guess—”

Angel had backed away to stand against the wall. He slid down it, sat against it, his soft laughter rising, his eyes on Tector.

“Hey, gringo. You take my share.”

Tector whirled, his hand flashing toward his gun. But Angel was faster. His gun was already in his hand and leveled. His lips spread wide. His tone was a mocking whine.

“Don’t kill me, gringo. Take my share of the loot but don’t kill me—please.”

Tector stood undecided, tense, his clawed fingers inches from his gun.

Pike said in derision, “Go ahead. Pull it.”

Tector continued to stand, his eyes riveted on Angel’s hand. His brother was ready and on the verge of trying beside him.

Pike’s voice held weary contempt: “Go on, all of you—fall apart. Throw in the towel. A hell of a bunch this is.”

Dutch eased the moment, saying, “Let’s walk soft, boys.”

The Gorches sagged slowly from their razor edge. Angel smiled and slipped his gun back under his belt. Lyle still watched him but Tector glanced at Dutch, flung his hand away from his holster, walked off a few steps and dropped heavily to the ground, one knee bent, his arm hung over it. After a moment his brother joined him. Sykes picked himself up, went indoors with his message to the woman, then came out and began to build a fire.

The light was going.

They watched the old man through a heavy silence. Dutch, Pike and Angel were one side of the ragged circle, the Gorch brothers on the other.

Sykes dug a bottle from his pocket when the flames took hold. He took a drink and passed the liquor to Dutch. Dutch drank, looked at the bottle, considering, then held it toward Tector. Tector, still sullen, hesitated, then rose and came for it. He had his drink and took the bottle back to Lyle. Dutch stretched, easing his shoulders, spoke to Pike.

“Well, what’s our next move?”

Lyle had grudgingly taken the bottle to Angel, and Angel brought it to Pike. Pike drank slowly, thoughtfully.

“You say the grub is short.”

“Gone.”

“We can’t get any across the line. I guess Agua Verde is about the closest place. How far there, Angel?”

“Three days maybe.”

Tector growled, “What are you going to use for money, these?”

He picked a washer out of the dirt and threw it at Pike’s face.

Pike’s hand snaked out to catch it, toss it aside.

“Sykes, did you get the horses?”

“Sure. With extras—even for the boys who didn’t get back.”

“We’ll take them all, sell them in Agua Verde. Good thing about a horse, you can always sell it in this country—unless somebody steals it from you first. Like you got these.”

“Then what?”

“We’ll find something. Look around and make some plans.”

Lyle barked a short laugh.

“You planned this one real good. Got us shot up for a pack of lousy washers. That was a great pitch you gave us—big job—enough to make it our last before we’d head south and live high. We spent everything we had getting ready for San Rafael. Now we ain’t even got grub.”

Pike tipped the bottle into his throat. The liquor was easing his aching body and his mood.

He said drily, “You spent your time and money running whores in Hondo while I put mine into setting up for the strike—but at that it turns out you were smarter.”

He had struck a note that worked. Lyle suddenly chuckled.

“You was out wasting money buying uniforms and working up plans while me and Tector was—”

He broke off, laughing. Dutch joined him.

“While you were getting your bell ropes pulled by Hondo whores.”

Dutch always found it easy to laugh and Lyle’s convulsions infected him. He roared. Then the rest of them were caught up. Even Pike joined in, knowing that it was all right. They were together again.

The old Mexican came to tell them the food was ready and they trooped around the house to where a cooking fire burned under a black pot of beans and boiled beef. The old woman was there, her full skirt tucked up into its waistband, slapping tortillas into flat, round cakes on her bare buttock, tossing them to her boy to place on the hot flat stone. The area of the hip she used was a lighter color than the rest of her brown skin.

The beans were blistering hot with chili but none of the men complained. They had long ago gotten accustomed to the fiery Mexican diet. The leathery tortillas were chewy and filling.

Afterward Angel went for his guitar, brought it out and found a place apart in the dark yard. He played softly for himself, singing in a nostalgic tone the old love songs of his country. The Gorch brothers lounged against the adobe wall, the day’s heat still trapped there welcome in the chilling night.

Pike and Dutch took their blankets into the shadows and rolled into them. Pike lay looking up into the starred face of the sky, listening to Angel, too tired for sleep. His leg throbbed with a constant pain only partly dulled by mescal.

He said finally, “You awake, Dutch?”

“Yeah.”

Dutch was a dark mound, hardly visible three feet away. His eyes were closed, his ears probably tuned to the music of the lonely guitar.

“Didn’t you once run a mine in Sonora?”

“I helped run a little copper property. Nothing there for us. Not even wages. It ain’t working now.”

Pike shifted in his blanket, unable to make himself comfortable.

“Why in hell did you quit?”

Dutch chuckled.

“Why in hell do you keep going?”

“I don’t know any better—maybe I don’t want to know better. Hell, I wouldn’t have any idea of what to do with better if it was poked into my eye with a sharp stick.”

“You never gave it a chance, Pike.”

Pike was suddenly angry.

“I threw away more chances in one year than you’ll see in your life. But that doesn’t mean you have to be a damn fool like me.”

Dutch sat up.

“You’ve got a halfway hard mouth, partner.”

“What do you want me to say?”

“Nothing.” Dutch lay back. “Just don’t read me no lectures.”

They lapsed into silence. After a while Pike spoke again.

“This was going to be my windup. I’m not getting any younger these days. I’m like the red-headed lady said to the white-haired judge—I only got so many miles left in my backside, Your Honor, and I aim to keep it moving while I’m young enough to feel what it’s there for.” Dutch rumbled a low laugh and Pike added in

a far-off tone: “I’d like to make just one more good score and then back off.”

“Back off to what?”

Pike only sighed and Dutch pressed him.

“Have you got a real idea for that next try?”

Pike lay a long time thinking, his eyes on the distant stars.

Finally he said, “The army’s got troops spread all along the border. Those boys get paid. And we’ve got uniforms.”

“Sure. But how do we learn when? That information is hard to come by.”

“I know. But I’ll get it. I’ve got to collect for the uniforms. Besides, there’s nobody else in this part of the country has anything we want. Nobody but the railroad—and they’ll be watching close for us now.”

“The army’s tougher to go up against than the railroad.”

“Sure.” Pike’s laugh sounded more like himself. He was never happier than when he had a difficult problem to solve. “I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Dutch smiled in the darkness, said with curiosity, “You must have hurt that railroad plenty before I knew you.”

“I hurt them.” Pike chuckled at his memories. “That’s why Harrigan went to so much trouble to get us.”

“Who’s Harrigan?”

“A proud and stubborn man. I saw him on that roof this morning. He had his ways of doing things and I made him change them. When you do that to a narrow man you make a lifelong enemy. He can’t live with the thought. He’s got to break you just to prove he’s right. There’s a hell of a lot of people, Dutch, can’t bring themselves to admit they’ve ever been wrong.”

“Like you say—pride.”

“They can’t ever forget that pride—or learn from being wrong.”

Dutch sounded thoughtful.

“You and me—did we learn anything by being wrong today?”

“I hope to hell we did.”

He broke off as Sykes materialized out of the shadow and put a cup of coffee in Pike’s hand.

“Heard you yakking. Make you feel better.”

The old man stood for a moment, companionable, then angled off toward his own blanket. Dutch stared after him in distaste.

“How’d you come to pick up that old spook?”

Pike was sipping from the cup, his eyes over the rim following the dimming shadow of Sykes, looking backward into the past. His voice was soft.

“That old wreck was one of the great gunmen twenty years back. He used to ride with Deke Thornton and me. He killed his share and more—around Langery.” His lips relaxed, eased up at the corners. “Those Swede immigrants down there—they were so scared of him they’d starve rather than take the risk of riding into town to buy beans for their kids. And there wasn’t a sheriff in the country who didn’t look the other way when Freddie rode by.”

He took a solid swallow of the coffee and spat it out immediately, cursing.

“The old bastard ain’t changed much. Only now he does his killing with coffee.”

He hurled the cup away, curled determinedly into his blanket and shut his eyes. Angel’s guitar across the yard, his trailing voice, laid a wishful pretense of peace over the Wild Bunch.

CHAPTER SEVEN

The new day again broke hot. All days were hot on the border at this time of year. The men rolled out of their blankets, stripped off the uniforms and went into the room they had appropriated in the rancho for their own clothes, trail-stained and worn into comfortable flexibility.

Dutch peeled the stiff khaki from him and threw it to the dirt floor, swearing.

“Idiot army must be crazy. Ship their soldier boys down here to chase bandits and dress them up in cast iron to fry to death in the sun.”

“Just hang on to those duds.” Pike spoke to the whole group. “Stick them in your saddlebags. We may use them again.”

Dressed for riding, they gathered again in the yard, saddling, bringing up the remuda from the corral.

The Mexican family watched the preparations. The outlaws had given them precious food through the weeks of their unsolicited visit but the old man was very glad to see that they were leaving. With the instinct of his kind he knew that these were violent men and that violence followed wherever they rode.

Pike Bishop ignored them, calling Angel aside.

“Your country up ahead. You say it’s three days to Agua Verde. Tell me about it. Is there water?”

“At San Carlos, yes.”

“What’s San Carlos?”

“A hacienda. A big one—beautiful. It was great before the civil wars. Then the owners ran to Mexico City and left the peons to look after themselves. What has happened since I do not know. But there is water.”

The more Pike saw of Angel the more confidence he had in the man. Angel was level-headed, hard-fibered, yet he wore the mantle of gunman lightly, showed no unmanageable turbulence. He had not panicked in San Rafael and he was good with his gun, his horse.

“Will there be food there?”

Angel shrugged.

“Who can say? The peons are very poor. The bandits steal whatever there is.”

“We’ll find out. Maybe we can pick up a rabbit or a rattlesnake on the way to keep our bellies off our backbones. You know the trail. You lead.”

Angel’s smile flashed, the teeth showing white and strong. He swung with an animal grace, stepped to his horse and roweled it out of the yard.

Pike mounted, favoring his leg, hiding his grimace. The Gorch brothers drifted into line behind him and Dutch and Sykes rode herd on the extra animals. Those were all the bunch had of value. Whatever they could get for them in Agua Verde would have to support them until they found a new place to strike.

Pike trailed Angel without really seeing him and without real consciousness of the train behind him. The past crowded on him. Everything had been different—the land, the women, the raids. Living had been simple and good. Choose a bank, a stage, a train. Hold it up, rifle the box, ride off to the shelter of pleasant hills.

Now the north country he had known was closed to his kind. Highways, better railroads; telegraph lines laced the west in a treacherous web. Let there be a holdup and the law for miles around was instantly alerted. And the new automobiles were another threat. They could not go across the country like a horse but a man in a gasoline car could cover in hours a distance that would take a horseman days.

He sighed. He had hardly noticed how he had been driven south, out of the good, green, watered land to this thirsty waste. The only virtue it had was one of being a no-man’s land where fighting had disrupted all law.

Bad as the heat-shimmering land was, it grew worse. They rode through broken desert scantily spotted with low brush, tufts of cholla cactus like grey tarantulas poised to jump. Small naked tumbles of black rock rose ragged between the growth. The trail was a thin, uncertain, twisting thing, wavering, seeking the easiest path among the hummocks of trees, only the branch tips sticking above ground, the trunks and roots reaching deep into the sand toward underground water. It was so crooked that a man could only tell his direction by where the beating sun hung.

Far ahead, not more than a shadow against the sky, rose mountains that looked soft from here. They were not soft. Pike Bishop had been in them. He hated them. Eerie peaks, towering bald and cruel. Only the Indos could find a living there, the descendants of early slaves used by the Spaniards to work the fabled mines.

The mines were lost. The work stopped when the slaves rose and murdered the managers, the priests and wiped the locations from their minds so that they should never be reopened.

But the treasure roads remained. Roads of pain and death snaking through the impossible barrier of the range. Paths worn deep in living rock by the sharp hoofs of burros driven by the thousands in pack trains, bearing a river of silver from the mines to the coast for transshipment to the voracious king of Spain.

Pike shivered a little at memories of his time here, the superstitious whispers, the sensation of being watched by eyes he could not see, of hearing calls and whistl

es from mouths he could not locate. The mountains were filled with ghosts, and Pike Bishop did not like ghosts. He had made too many of his own.

They crossed a series of raw gashes, arroyos torn out by recurring flash floods that raced across the desert waste from cloudbursts high in the hills and were swallowed immediately in the thirsting sand.

Angel pulled up at the rim of one deep gouge. Pike rode up beside him. They looked down the wall. It was sand, very loose, the footing bad. They could not ride down. They could not drive the remuda down.

He ordered a dismount to tie the loose animals on lead ropes. Each man took a string of horses. Pike started down on foot, sideways to the bank, leading his horse and one other.

Angel waited until Pike was down, then followed with three animals. Lyle, Dutch, Tector did not wait until he was clear but came on each other’s heels. They were all still on the slope when Sykes stepped off the rim. The old man had five horses on his rope and they were skittish at being tied together.

Pike, watching from the wide, flat pebble-strewn bottom, saw Sykes’ feet sink into the slipping sand. The horse directly behind him stretched its neck and set its hoofs, refusing to move. Sykes yanked his line. The horse lurched forward against its will, its forefeet dropping over the edge. Frightened, it struggled, slid downward, caught Sykes in the back and knocked him ahead.

Sykes lost his balance, yelled, tried to free his feet from the stuff around him, could not and pitched over. He landed hard against Tector, knocked him off his feet and started a domino reaction. Every man in the line went down, dropping his lead lines, slipping and rolling in the sand slide that came with them. Men and animals hit the bottom in a cloud of dust and thrashing hoofs, curses and confusion.

Pike jumped away as they came, wrenching his bad leg. He ignored the pain as the frightened, plunging horses broke free and headed up the arroyo. He ran, waving his hat, turning them back and they stopped, shuddering, shifting nervously as the men untangled themselves and climbed out of the slide.

Tector was blind with dust and rage. He scooped up a rock and threw it at Sykes, caught him in the head.

Sykes went down like a poled ox and lay still on the hot sand.

Pike jumped for Tector, caught his shoulder, spun him around.

The Wild Bunch

The Wild Bunch