The Wild Bunch Read online

Page 3

“Not now.” He had the boy by the shoulder, his fingers biting to make an impression. “A shot now will bring a hornet’s nest down on us.” Crazy Lee had failed his test. He would not do to ride with, that was clear. Pike let him go, spoke to the woman. “You might as well save your breath with all that racket in the street. Nobody can hear you.”

She glared at him and Dutch laughed across the counter.

“Ma’am, I wish I had the time to teach you what women are made for.”

Pike walked to the quaking paymaster huddling with the clerks.

“Come along, old man. Get the safe open.”

The man shivered.

“I haven’t got the combination.”

Pike had met liars before. He understood them. He raked his gun barrel down along the narrow head. Blood spurted above the ear and the man slumped. He was not out.

Pike said, “Get it open before I really crack your skull.”

The man wiped blood from his eyes, scrambled to his knees and crawled to the safe. He rotated the dial, right, left, right, twisted the handle and pulled open the door.

On the front of the shelf was a box of loose coins, perhaps a hundred of them. Behind it were piled sacks stamped with the railroad’s mark. Pike shoved the kneeling man away and hauled out a sack. It was satisfyingly heavy. It clanked as he tossed it to Dutch.

“All right, boys, load up.”

One by one the outlaws came with their saddlebags, filled them with sacks and moved back out of the way. Dutch emptied the box of loose coins into his bag for good measure.

Pike did not join the loading. He returned to Angel at the window. The din outside was deafening now. Trombone, cymbals and women’s determined voices chanted an old hymn.

Let us gather at the river . . .

Behind him Crazy Lee, keyed higher by the booming drum, the blaring horn, abandoned his post and came leaping to watch and listen. The woman sneaked a glance at the outlaws around the safe, saw that their attention was not on her and sped crabwise toward the door.

Angel caught her movement from the corner of his eye, jumped for her and dragged her back. She stumbled, spitting at him, trying to jerk free.

“Trash. Filthy trash—take your hand off me.”

He hit her hard enough to send her staggering back against the counter. He followed her, grinning.

“Me, I had a bath three months ago.” He shoved her through the passage and back with the captive clerks. “Stay there as you were told. You try again to leave and we kill you.”

He paused at the safe to fill his own saddlebag, strode once more to the window. Pike turned away from it, anxious now to get his force moving. But Angel spoke a sharp warning and pointed to the roof of the building facing this one.

Pike whipped back. The top of the false front was a pincushion of rifle barrels.

“It looks like maybe we were expected, no?”

• Harrigan had been watching intently across the plaza. He saw Angel’s hand come up and point and barked a laugh.

“They’ve spotted us. Now they’ll check the back door. Get ready. Thornton, you—stand up so he can see you. He’s got to know it’s his old friend over here.”

Yes, damn you, stand up. Stand and show yourself for what you have been made into. Pay the whole price for your freedom. Pike Bishop will understand. And if Pike were in your position he would do the same . . .

Pat Harrigan was on his feet, bareheaded, grinning. Thornton rose beside him, swept off his hat and rested his gun butt on the top of the wall, squaring himself, looking levelly through the window.

• Angel swore a Spanish oath. It seemed ridiculous to him that the men on the roof would so expose themselves. They invited being shot. He began slowly to raise his rifle.

Pike saw Harrigan first and recognized him. The man who stood up beside him was hauntingly familiar. And then he knew. Deke Thornton. But changed. Older. His face deep lined.

Seeing those two together told Pike the full story instantly. The trap was crystal clear. Harrigan hated him because of his raids on the railroad that had made Harrigan look the fool. And Harrigan was vindictive. He had turned his job into a personal vendetta. He had gotten hold of Thornton, forced old partners to play against each other. Harrigan had turned Thornton into a bounty hunter.

The realization went through Pike like a searing knife. It pointed up the wreckage of his life. His youth, the great wild days were gone. They could never be recaptured.

He saw Angel’s gun at his shoulder and said sharply, “No. Start shooting and they’ll make this place a sieve. They’re not in a hurry. We’ll make it.”

He did not explain why Harrigan was not in a hurry, although he knew. He had always been able to read the railroad man’s mind. At least well enough to survive until now.

“Keep watch.”

He left the window, pushed through the men now crowded behind him, made nervous by Angel’s discovery of the ambush. He strode to the rear door, knowing what he would find outside but needing to be sure. A habit of thoroughness had kept him alive through many other close scrapes. And so far he had never been caught.

Conscious of Dutch behind him, heavy saddlebag in one hand, gun in the other, he cracked the door enough to see into the alley that ran behind the building. It was bordered by adobe and frame structures with vacant spaces between, hard-packed, sunburned earth littered with heaps of trash, old cans, broken bottles turning purple from long exposure to the desert sun.

Pike’s attention sought the building corners, the occasional barrel, finding the hidden men betrayed by a shadow here, the glint of sun on a rifle there. Yes, the cage had closed. He shut the door and threw the bolt.

Dutch had had his view over Pike’s shoulder.

“Son of a bitch.” He said it softly. “How did they know we were coming? That Crazy Lee kid let it leak?”

“No.” Pike discarded the question. It did not matter how Harrigan had known. Speculation was a waste of time. The thing now was to get out with a whole skin.

He went once more to the front window, assessing the street, the chances. The parade had stopped. The head of it, the band, was at the door of the saloon. The trombone player had stopped his noise, faced the women and was arguing about something Pike could not hear. The hecklers and other citizens drawn by curiosity had grown to a crowd.

Crazy Lee pressed close at Pike’s elbow, his ferret face quivering with excitement.

“Ain’t we going out the back way, Pike?”

Pike’s eyes narrowed on the boy.

“We can’t, Lee. The alley’s full of guns. Besides, when I leave a town I like to have a horse between my knees—and the horses are across the street.”

Lee giggled.

“We give them a show, huh? That’s good. I’ll go first, yelling like a ’pache and—”

Pike put a restraining hand on the narrow shoulder.

“We can’t leave these prisoners at our back without a guard. That’s your job. You watch over them while we make a run. We’ll make the horses and ride out. That gang will be so busy with us they’ll never think there’s anyone left in here. You trail out when the coast is clear. Think you can hold the prisoners alone?”

The boy stuck out his chicken breast, his lips spread in a wide grin.

“I’ll hold ’em till hell freezes over, Pike. Do I kill ’em before I leave?”

“Not unless you have to. We’ll take the woman and the paymaster with us. You ought to be able just to knock out the two clerks and walk away.”

He did not know whether or not the boy would get clear. He was not sure any of them would get clear. But at least the kid was as well off staying in the building—with a chance to slip away during or after the commotion—and Pike did not want him along any longer.

Pike raised his head and his voice.

“Here’s the action. Listen good. I’ll shove the paymaster out front first. That should hold them for a minute—give us time to dive into the crowd. Spread out in

the square, and hike for the horses. I don’t think they’ll shoot with all those women around us but don’t bunch up and give them a solid target. Ride out in singles. Separate. We’ll meet at the ranch.”

He strode around the counter as he talked. He pulled the paymaster to his feet.

“Dutch, come get the woman. Use her as your shield.”

“I am not going out there.”

The woman dropped down, sat flat on the floor, frightened now.

Dutch Engstrom rounded the counter, bent, got one thick arm around her body under her armpits and swung her clear off the floor. Dutch was laughing, happy with the game ahead.

“Dead or alive, ma’am.”

Pike swung the paymaster around, yanked the man’s fist up into the middle of his back, pushed him ahead. He waited at the door until the others were grouped behind him, pulled open the door and hurried the paymaster out among the milling ladies. Dutch and his shield came at Pike’s heels.

The women, now shaking fists and shouting at the trombone player who blocked the saloon entrance, paid little attention to the rushing figures erupting from the railroad office. Jostled by men in military uniform, they gave way impatiently, engulfed in the frustration of their mission.

Pike was running, dodging through them, trusting that Harrigan would not risk shooting into a body of women.

He did not hear the rifle crack. The bells in the tower of the little white adobe church broke into their carillon. The paymaster in his hand jerked, slumped, hung in Pike’s grip and dragged Pike with him to the ground. He let go and stood up, running, weaving, bent low.

• On the far roof a bounty hunter’s gun muzzle smoked and the shot he had fired became a signal. Guns blasted all along the line.

Thornton and Harrigan yelled and fought, trying to stop the hunters. Under the piercing ringing of the bells they were not heard or heeded. Every rifle on the roof was spitting lead toward the distant doorway.

Whether the bells distracted the men or whether their aim was normally bad, the shots were wild. The outlaws poured into the street. The doorway emptied. The soldier figures scattered like quail and the carillon abruptly stopped. The sound of hammering guns racketed through the square. Screams took the place of shouts among the paraders. Women ran. Hysteria spread like prairie fire. Hecklers dived for shelter, were crushed in doorways. Children shrieked and dodged among the flying feet of panicked adults.

After the carillon the tolling of a single, deep-toned bell took up in slow rhythm, rolling like thunder over the growing melee. Tolling the time. Eleven o’clock.

Women were hit and fell. Men were hit. Children were trampled.

• Marshal Simpkins and his deputy, Fray, blocking the door of the Lone Star, were crammed against the wall. They were unable to break through the mob pushing against them.

Simpkins thought at the beginning that some heckler had started shooting up the air to break up the temperance parade. He dropped his trombone and pulled his gun, looking over the heads bobbing in front of him to stop the damned fool. Then he saw the bright flashes from the roof.

The scene suddenly made no sense to him. Most of the males of San Rafael were openly against the temperance society but the men on the roof were either drunk or crazy. He aimed at them and fired his short gun, helpless to make any other move.

Deke Thornton was not firing. He wrenched a gun from Coffer’s hands, flung it to the street and turned on T.C. Nash.

But he got no help from Harrigan.

Harrigan’s gun was up, sweeping across the mad scene below, trying to pick out Pike from among the running figures.

• In the window of the railroad office Crazy Lee Stringfellow was dancing with excitement. Never in his life had he seen anything like this. Dancing, marching up and down, waving his gun, he was singing in a high, cracking voice. Singing the song he had learned in his childhood, the hymn to which the temperance women had come marching.

“Shall we gather at the river . . . shall we . . . Hey, you two,” he waved the gun at the clerks crouching against the wall. “You know that song? Sing out. Sing out.”

Their voices rose, wavering with fright, making a prayer for help of the hymn. Crazy Lee was delighted.

Then a bullet from across the square broke the window glass and it crashed in. Crazy Lee crouched below the sill, seeing the bright flashes from the roof and giggled. But the men there were keeping out of sight and he lost interest. He looked across the frantic square. The booming of the big bell sent tingles through him.

He sorted out Tector Gorch with the horses, waving his brother to him, saw Tector spin as a bullet struck his shoulder but did not knock him down. Tector threw up his gun, blasted at the roof and a bounty hunter pitched over, down, bounced on the walk.

Lee saw Lyle run in, catch the reins of the rearing horses, fight them down.

Lyle was hit and Tector jumped to help him. He pushed his brother up to the saddle, mounted and kept shooting upward, all the while hanging on to the horses for the others.

Pike appeared out of the mob, Dutch and Buck close behind him. They threw themselves into saddles and the five wheeled out, separating through the scattering crowd, looping toward the mouth of a side street. The other boys did not show up. Crazy Lee went back to his singing.

Dutch, jumping through the office door after Pike, had shoved the woman aside as they reached the parade shelter. He dodged in Pike’s wake, his saddlebag in one hand, his gun in the other, shooting at the roof as he ran.

At the horses he counted the thinned gang, saw Pike swing up and grinned. Pike was all right. They weren’t yet through. As he swung his horse and drove through the square he had quick glimpses of uniformed men sprawled on the ground. He saw Frank die and counted again. But most of his attention was on trying to ride through the scramble that clogged his way.

• Deke Thornton still had not fired a shot but now, through the thinning ranks, he had a view of Pike riding away from him. He raised his gun, hesitated, sent a bullet whipping after the man he had promised Harrigan he would kill.

Pike’s horse stumbled over a fallen body, caught itself and pounded on.

Thornton had missed.

Harrigan was swearing in raging frustration.

“You’re a hell of a shot. You were supposed to hit him. Well, let’s get down and see what we did get.”

• The mouth of the side street was blocked by struggling people. Pike Bishop shoved his horse against them, forced a passage. His riders converged behind him, followed him through. He glanced back to see who was there, found Dutch on his heels, the two Gorches, Buck and Angel. Only the six of them were left. The rest were wounded, dead or captured. He did not know and had no time to find out.

His glance showed a bloody stain on Tector Gorch’s shoulder, a bleeding crease along the side of Lyle’s head. He called to them.

“You two all right?”

“Sure,” they answered together. “Go on. Go on.”

Beyond the intersection were only a few fleeing citizens and Pike’s survivors spurred their animals. A man appeared in a doorway, leveled a rifle and fired at them. The bullet nicked the nose of Dutch’s horse and it bolted, swerved out of the road and in through the open door of the gospel tent.

Dutch could not control the animal. It galloped down the narrow aisle, the flying hoofs knocking chairs out of the rows, bumped blindly into the support pole at the rear, jarred it from its vertical position and the heavy canvas billowed down around Dutch.

He fought it. His horse reared and nearly threw him. Pike drew his knife and slit the rotten cloth. Dutch kicked the horse and it shot into the open, tried to run away. Dutch reined it down, got it under control, turned and spurred after the others.

The screaming, the confused shouts dimmed as they reached the edge of town. The street was empty except for a wagon drawn up near the railroad station.

A boy of thirteen on the high seat looked toward the square. He saw the riders pelting toward him, heard the terror

in the square and reached for his father’s shotgun behind the seat and sat waiting.

He was scared but he brought up the twin barrels with grim determination as the riders swept past him. He almost missed getting the gun up in time.

Buck, last in line, saw the gun being raised and tried to pull the forty-four he had returned to its holster. But the shotgun beat him to it. The range was too far to kill but Buck threw his hands up against his eyes, doubled forward in his saddle.

Tector looked back at the sound of the explosion. He swung his horse around and rode back at the wagon, yelling. The party hauled in, turned, saw the boy fumbling to reload, saw Tector shoot him twice. The small body pitched forward onto the wagon tongue.

Tector wheeled again, pleased with himself, but back at the square a group of men on foot, shooting, poured into the side street.

Pike swore.

Dutch said sharply, “Let’s get out of here.”

Hidden by their own cloud of dust, they rode out, Angel catching the reins of Buck’s horse and hauling it after him. Buck rocking in the saddle.

They passed the sign that had welcomed them to San Rafael and headed south toward the border.

CHAPTER FOUR

History would call it a massacre and no one in that square that day could argue.

Wainscoat, in his office at the city hall, heard the band and the singing as the parade wound around the square. He winced. Mary was going to be one mad female when Simpkins wouldn’t let her bust in on Bill Jordan. He heard the first shots and winced again. Must be the women were giving the marshal an argument and he was firing into the air to assert his authority, scare them into behaving.

Then he heard the screaming.

He ran from his office, knowing a cold foreboding but unable to guess at what was happening in his town.

A hall door opened as he passed and a man jumped out, bumped into him, caught his arm to keep his balance, then ran beside him. Wainscoat recognized Benson, the rancher, coming from the tax office.

They reached the turmoil outside and stopped, shocked into disbelief. Horses were whirling into Third Street. Women and children on the sidewalks clung to each other, sobbing. Men in and out of uniform lay unmoving in the dust of the plaza. But the horror was in the still, white figures, the dresses of the parade women no longer white but bloodstained, marked by the dusty shoes that had tramped over them in the wild scramble for safety.

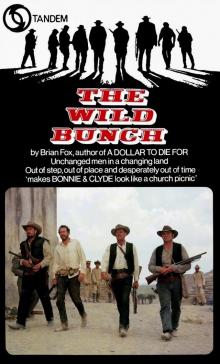

The Wild Bunch

The Wild Bunch